In this post I return to more mainstream matters for physicians namely the process of being licensed to work as a doctor in the UK and whether or not that process links to professionalism.

What I say in this post applies to career-grade [consultant and SAS (staff, associate specialist and speciality)] hospital doctors. Licensing of trainees is similar but with some significant differences which I plan to cover in a later post.

Different health systems, different ways of monitoring doctors

To give some perspective I’ll start briefly with how doctors are licensed in different countries.

Except possibly in failed states where medical licences are the last thing on anyone’s mind, every doctor in the world requires permission to practice from the national or regional medical licensing agency covering the territory in which they work. Sometimes this function is delegated to a professional medical society.

Such agencies have the power to review and even to withdraw a doctor’s licence to practise if they are satisfied that the doctor’s performance is impaired.

Each medical licensing authority has its own way of assessing the performance of the doctors whom they licence to practise, reflecting the legal and medical systems in their territory.

Whatever their health system, populations in the accountable democracies across the world are increasingly demanding that their elected representatives ensure that their doctors are competent and are held to account for their actions.

Surprisingly, some “accountable democracies” (countries where public officials and bodies are held accountable to the public and to their parliament) have relatively limited external review of the competence of their doctors. Some are in the process of expanding their reviewing mechanisms while others trust their doctors to regulate themselves.

Additionally, in many countries where most patients pay for their medical care directly or through their own insurance, licensing authorities adopt a low profile in the oversight of doctors. Censure of underperforming doctors is left largely to personal litigation by patients or to the criminal law.

Conversely, in countries where doctors are employed directly or indirectly by the state, governments tend to have a much more active role in medical supervision particularly if the state is responsible for compensation for medical negligence as is the case in the NHS.

The medical licensing system in the UK

The medical licensing authority in the UK is the General Medical Council (GMC), which is accountable to Parliament. By law its main objective is to “protect, promote and maintain the health and safety of the public”.

The UK medical licensing system requires ongoing review of individual doctors’ performance for the duration of their careers. Doctors have to submit evidence of their competence and conduct to the GMC at what feels like very frequent intervals.

This is separate from the system of review of hospitals and general practices by external inspectors, a task that in the UK is performed by the Care Quality Commission (CQC).

However the reviewing system for individual doctors is highly dependent on effective organisational governance (which is assessed by the CQC). Inept or dishonest doctors generally find that well-governed healthcare organisations are uncomfortable places to work.

Employment of doctors in the UK

In the UK the overwhelming majority of doctors are employed by or contracted to a medical organisation of some type such as a hospital, private health corporation, pharmaceutical company or medical charity. General practices are businesses that are owned by the GP partners.

Apart from those doctors working for private employers or the relatively–few working for themselves in full-time private practice most doctors in the UK (including GPs) work for, or are in some way contracted to, the National Health Service (NHS) . This is a wide-ranging service funded out of general taxation, covering both preventive and curative medicine.

Appraisal and revalidation of doctors in the UK

The UK has a complicated system of medical re-licensing that I will describe as concisely as I can.

In most countries doctors are assumed to be safe to continue in practice until proved otherwise. That is not the case in the UK.

Since the end of 2012, all consultants, GPs and SAS doctors working in Britain have had to repeatedly prove their competence over repeated five year cycles of revalidation, an invented word used to describe the process of proving one’s fitness to continue in practice.

This re-licensing system came into being gradually over the years, driven by periodic medical scandals.

All organisations in the UK that employ or contract doctors are registered with the GMC as Designated Bodies.

From the doctor’s viewpoint a Designated Body is an organisation that can help a doctor with revalidation.

In each Designated Body a Responsible Officer (usually its Chief Medical Officer) is in charge of managing the revalidation of doctors registered with that Body.

Much of the evidence for each revalidation comes from annual appraisals conducted since the doctor’s previous revalidation by peers who are acting on behalf of their Designated Body. Appraisals are also managed by the Responsible Officer.

Other sources of evidence such as reports from tribunals will also be considered in the revalidation process.

At the end of every five year cycle of appraisal the GMC receives the Responsible Officer’s recommendations about whether or not the doctor should revalidate, based upon cumulative evidence from their appraisals and other sources over the previous five years.

The GMC then confirms, makes conditional or withholds the doctor’s Licence to Practise. This is an official term used by the GMC which is why I have put it in capitals.

Doctors in temporary (locum) posts have the same appraisal and revalidation requirements as doctors in substantive posts. Similarly, doctors who work entirely for themselves have to find a Designated Body (usually the private hospital group in which they do most of their work).

In order to avoid an abrupt yes/no decision about a doctor’s revalidation at the end of the five year cycle, any concerns about that doctor should have been identified and dealt with by the Responsible Officer and their team long before appraisal.

The need to supply supporting information for appraisal

At each appraisal every doctor has to supply evidence (which the GMC refers to as “supporting information”) on an appraisal form that they submit for scrutiny, initially by the appraiser and then by the Responsible Officer or their appointee.

This evidence covers the broad areas of (i) continuing education and professional development, (ii) satisfactory involvement in safety and quality improvement processes, (iii) receipt of any complaints and involvement in significant (adverse) events, (iv) multisource feedback from patients and colleagues, (v) achievements, challenges and aspirations, (vi) evidence about the doctor’s probity, health and wellbeing, and (vii) a personal development plan.

At the end of the appraisal the appraiser summarises the evidence on the appraisal form in four overlapping Good Medical Practice “Domains” required by the GMC. The doctor has to supply satisfactory evidence for each Domain.

The standard version of the appraisal form is known as a MAG form and is available online for illustrative purposes. (Please note that this interactive .pdf form has to be downloaded then opened from its target folder; it cannot be opened directly from its weblink).

The system works - provided that everyone does what they are supposed to do

The UK’s revalidation process is rigorous in most respects. However it relies on the diligence with which the Designated Bodies conduct and supervise their appraisals and follow up on any concerns about their doctors at the time that concerns are raised rather than at appraisal.

The Designated Bodies regularly discuss concerns raised about individual doctors with their GMC Employer Liaison Advisers.

Doctors in the UK often have several roles. For example many consultants work both for the NHS and on their own behalf in private practice.

Those who supply inadequate annual evidence in the four GMC Good Medical Practice Domains in each of their roles as a doctor (which could include working as a hospital specialist, private practitioner and medical journal editor) risk withdrawal by the GMC of their Licence to Practise. The same censure applies to doctors who fail to engage with the process of revalidation.

An important part of the evidence that UK doctors are safe to continue in practice is provided for each doctor by their patients and colleagues (including health professionals from allied disciplines such as nursing and physiotherapy, as well as from medical secretaries and ward clerks) in five-yearly structured confidential multisource feedback assessments containing standardised questions.

Respondents are asked give their views on the competence and conduct of the doctor.

The flaw in the appraisal process

I have been both on the delivering and receiving end of many appraisals and I was appraisal lead for my hospital for nearly six years. I am thus familiar with the strengths and the shortcomings of the process.

The core problem with medical appraisal in the UK is that it is intended both for the personal development of the appraisee and as a performance review. I am far from the first to recognise this as a problem.

The problem would be solved if the appraisee’s performance and conduct were dealt with before the appraisal by senior medical managers. I do not believe that such issues can be assessed by a single peer-appraiser.

The shortcomings of the GMC Good Medical Practice Domains when used in appraisal

I think that the four Good Medical Practice Domains as they stand are a wise and well-balanced statement of the standards required of doctors. However their practical use in appraisals is challenging.

One reason is that many sensitive items within the Domains are implied questions about whether or not the appraisee is meeting the required standards of performance and conduct. The answers really need to be be supplied by medical managers prior to the appraisal.

Breaches of the required standards in Domain 4 (Maintaining Trust) as well as in some areas of the other Domains are rare but often carry disciplinary implications.

These sections of the appraisal form that request answers to questions such as “does this doctor act with honesty and integrity?” would be better completed by the Responsible Officer or their deputy with “white space comments” rather than tick-box answers.

At the moment the answers are left to the appraisee to complete and the appraiser to confirm.

Additionally it is extraordinarily difficult for the appraisee to bring good evidence that (for example) they “treat patients and colleagues fairly and without discrimination” other than their multisource feedback, which they undertake only one year in five.

Furthermore if there were any suggestion that the appraisee on occasions did not treat patients and colleagues fairly and without discrimination, it would be a foolhardy appraiser who challenged the appraisee about that. Senior medical managers should discuss such issues with the doctor long before the appraisal.

Difficulty in allocating supporting information to the appropriate GMC Domains

Problems also arise because some types of evidence (“supporting information”) brought by the appraisee to their appraisal are difficult to match to the appropriate Domains.

This is because both within and between the Domains there is a lot of overlap. The appraisee thus ends up citing the same evidence (most commonly the results of multisource feedback) in different Domains.

Additionally it is difficult to infer from the headings of some Domains what evidence is required. For further clarification appraisees and appraisers have to look up a separate guide; few do.

Suggested solutions to these shortcomings

The present appraisal system is a compromise that followed challenging negotiations with doctors’ representatives.

Negotiations over any changes to the appraisal system are thus also likely to be difficult.

It is nevertheless a pity that an opportunity to comprehensively reform the system (and the GMC Good Medical Practice Domains) was lost at the time of the Pearson Review of appraisal and revalidation in 2017.

Appraisals using two appraisers (one or both of whom are medical managers) would make appraisals feel more significant to appraisees and are already being undertaken in some hospitals. However that is unlikely to become the norm because many hospitals struggle to find doctors willing to appraise their peers and part-time medical managers do not have the time to appraise all the doctors in their division.

Apart from moving currently-overlapping topics to only one Domain each, I believe it would be helpful to appraisees for their managers to review with them on a separate occasion any concerns about their performance including their outcome measures. If there were no concerns then a meeting would not need to take place.

The appraisal meeting would then focus on developmental needs and remedial measures required.

That would mean that the developmental aspects of the appraisal would remain dominant and would be led by the appraisee and their peer-appraiser.

The evidence from the appraisee’s managerial performance review and from the appraisal meeting should be merged into a reconfigured single appraisal form.

That would allow any legally-authorised body including any future employer to see the full scope of the doctor’s activity, performance and aims in a single document as well as remedial action taken by the doctor to correct any deficiencies in their performance.

Change is likely to be forced by the passing of time

The current appraisal system may anyway be outflanked with time; doctor- reported outcome measures that I discuss later in this post are becoming increasingly detailed and accurate and will gradually bypass the aspects of appraisal dealing with doctor performance unless the system is reformed.

Concerns about their performance including adverse outcome measures are increasingly being discussed with doctors separately from the appraisal process.

If the political climate were to grow more hostile to doctors in the future, appraisal might become no more than a mentoring exercise, regarded as pointless by appraisees and their clinical managers, with the real, daunting “clinical review” taking place in the manager’s office. The developmental aspects of appraisal might not survive in that scenario.

The appraisal process sometimes misses significant incompetence and misconduct

Despite the universal use of the appraisal process, troubling cases of incompetence and misconduct continue to surface in UK hospitals.

As an example, Ian Paterson, a surgeon, received a 15 year sentence some years ago for intentionally injuring patients (although of course he didn’t see it that way). This sentence was increased to 20 years in 2017 when he appealed against the severity of his original sentence.

Such cases “get through the net” if senior medical managers ignore repeated warning signals about a doctor’s competence or conduct and if discussion of large, difficult issues is avoided by managers and colleagues.

These failures reflect weak clinical governance within healthcare organisations, from the top downwards. The leaders of such organisations are increasingly being held to individual account for such malfunctions.

Appraisals conducted by single peer-appraisers who (i) feel uncomfortable about challenging their appraisees, especially those who go out of their way to conceal or minimise problems or (ii) have too cosy a relationship with their appraisee to discuss difficult issues, will often fail to highlight problems. This failure will be compounded by inadequate review of appraisals by senior medical managers in hospitals with weak clinical governance.

Appraisee statements of problems

To get around these problems in the hospital in which I worked, for several years each appraisee has been required to bring a statement to the appraisal that clarifies whether or not they have been involved in problems of the type that sometimes set a doctor on the path to competence and conduct hearings, both locally and at the GMC.

This statement is countersigned by the appraisee’s Clinical Lead who is encouraged to take advice from their Clinical Director if they are unsure whether to sign the statement or not.

The appraisee is required to answer questions in the statement about (i) failure to agree a job plan (often a sign of discord within a department or between the appraisee and their managers), (ii) numerous unplanned short term absences from work (indicating possible difficulty coping or being subject to external pressures that disturb the ability of the appraisee to do their job to a satisfactory standard), (iii) documented involvement in disputes involving medical, nursing or other colleagues (which can be a sign of bullying or discord within a department) or (iv) being the subject of any documented complaints, competence or conduct concerns identified in clinical governance meetings , by PALS (the NHS Patient Advice and Liaison Service) , through the Friends and Family feedback mechanism or through other documented third party sources including litigation or inquests, where the clinical care that the appraisee offered was at issue.

Other hospitals use similar statements. Used honestly and fairly these can provide a significant amount of additional evidence for the appraisal and inform useful discussion.

The sense of threat that appraisees may feel at supplying this information may be reduced if they know well in advance what they will be required to supply, especially if it has been discussed with their medical manager, and how it will be used.

What are adequate standards of competence and conduct?

This question runs through all discussions about clinical performance.

Incompetence and poor conduct have always been easy to recognise but difficult to define. Nowadays positive definitions of competence are being refined in many different hospital specialities through the increasing use of outcome measures.

These include not only outcomes reported by patients (the PROMS or Patient Reported Outcome Measures that I mentioned in my previous post) but also outcomes reported by doctors themselves.

Examples of doctor-reported outcomes include revision rates after joint replacement surgery supplied by surgeons published in the UK registry Registry, and performance of individual gastroenterologists against agreed key performance standards for colonoscopy.

Outcome measures remain imperfect as a gauge of competence

Outcome measures are relatively easy to develop for most interventional procedures, which are defined by the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence [NICE] as any procedures that are used for diagnosis or treatment that involve incision, puncture, entry into a body cavity, or the use of ionising, electromagnetic or acoustic energy.

However even in interventional specialities there is still a long way to go in establishing outcome measures that everyone agrees are fair and that accurately reflect individual competence.

Performance of physicians is difficult to evaluate

To complicate matters further, non-interventional hospital specialities often use the adherence of their doctors to quality improvement and patient safety measures applied across their department as a measure of individual clinical competence. Those measures are however not designed for assessment of individual competence.

I have found that the multisource degree feedback assessments of doctors that are performed as a requirement for revalidation are a very effective measure of competence and conduct. They work very well in internal medical teams. Other team members are free to (and often do) point out the strengths and shortcomings of their colleagues. Patient feedback may also be helpful in that regard.

For junior doctors in the UK the process of competence assessment is elaborate. Those of you who have done workplace-based assessments will know what I mean. I hope to discuss these in a later post.

Why go to all this trouble?

The number of underperforming doctors in the UK is very low relative to the total number of doctors. What then is the point of taking these elaborate measures to “catch only a few bad apples”?

The answer is in the apple barrel metaphor: the bad apples very quickly infect the whole barrel.

Just as importantly, to continue the metaphor, apples go bad in an environment where they are left untended.

The need for tending the environment in which doctors work is illustrated by the case of the surgeon Ian Paterson that I described earlier in this post who was able to get away with criminal behaviour.

The Responsible Officer and Chief Executive of that surgeon’s then-Designated Body are currently facing a GMC tribunal over charges that they failed to prevent patient harm. The Chief Executive allegedly failed to promote a blame-free culture for reporting clinical concerns and neglected to inform the hospital’s board promptly that the surgeon’s multidisciplinary team had been performing poorly for many years.

Professionalism

Adequate competence and good conduct are core features of professionalism although there is much more to professionalism than that.

Like adequate competence and good conduct, professionalism itself is easy to recognise but difficult to define. There are many definitions of professionalism but the one I developed for my own purposes when I was Head of the School of Postgraduate Medical Specialities in my regional deanery is

professionalism involves behaving in ways that show peers and patients that one is competent and trustworthy.

Immediately – visible behaviours suggesting professional trustworthiness are shown in the table below.

This definition is not foolproof because dishonest, insecure and incompetent doctors may cultivate “reassuring” behaviours to conceal their shortcomings.

Less-obvious attributes of professionalism

How does one go below the surface, to see the deeper qualities and values that doctors possess?

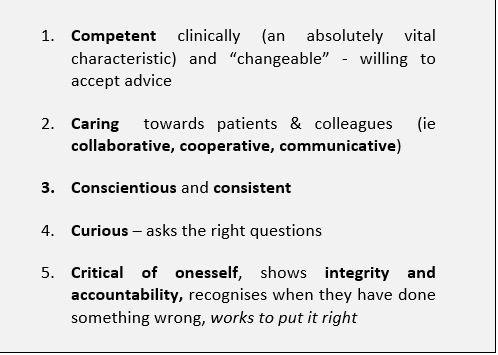

One hopes that all doctors would try to develop the less-obvious characteristics in the table below which may not at first glance be immediately visible to patients or to colleagues.

The first attribute (competence) is absolutely-required; the other four attributes are irrelevant without competence.

Five less-instantly recognisable attributes of the doctor who is regarded as trustworthy by colleagues and patients (The Five “Cs”)

The appraisal / revalidation system can give a reasonable indication of these deeper qualities in individual doctors, particularly via the anonymous multisource feedback questionnaires about their performance that doctors need to have completed by patients and colleagues every few years for their revalidation.

Humility and professionalism

I believe that the questionnaire currently-recommended by the GMC for multisource feedback on appraisees could be improved significantly by including more emphasis on something like the “Five C” attributes listed above.

These attributes have long been recognised; Sir William Osler, who in 1889 was appointed as the first Physician-in-Chief of the then-new Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore USA and who later became Professor of Medicine at Oxford University in the early 20th Century, identified humility as a key attribute of the good doctor; the humble doctor knows their limits.

Humility develops through accepting accountability for one’s work.

The “Five C” attributes are unfortunately also not foolproof; everyone in clinical practice will have encountered doctors who are very caring and conscientious but who have tried to conceal their own shaky competence by arranging excessive numbers of (often irrelevant) investigations and outpatient clinic appointments for their patients to boost their credentials as caring and conscientious doctors.

Patients are often very impressed by such actions. However the truth will always emerge if medical colleagues and other health professionals do not try to excuse repeated displays of incompetence because the doctor is very “pleasant” or caring.

Do appraisal and revalidation indeed link to professionalism?

Clearly they should,but they sometimes do not because of shortcomings in the appraisal process, in the Domains under which professional qualities are evaluated and in the governance systems of the hospitals in which physicians are appraised.

Separation of the conduct and competence aspects of the appraisal from the developmental aspects followed by merger of both in a single appraisal document would add considerable value to the appraisal.

Inclusion in the appraisal documentation of a statement detailing the appraisee’s conduct and competence signed by their clinical manager(s) will go some way toward correcting the current paucity of input from the appraisee’s clinical managers to the appraisal.

Despite its shortcomings the current appraisal system offers ample opportunity to assess and to reinforce the professionalism of appraisees.

Next post: Why our system for training physicians is so complicated