Medically-unexplained symptoms

What are “medically-unexplained symptoms”?

Various terms, often judgmental, have been used by doctors over the years to describe symptoms which have no physical explanation. Currently the somewhat-unsatisfactory but non-judgmental term “medically unexplained symptoms” is often used. Neurologists often talk about “functional disorders”.

The term “non-organic” is also widely used for these conditions.

The process leading to a diagnosis of medically-unexplained symptoms is usually as follows:

1. People consult doctors with symptoms about which they are concerned.

2. In some cases the cause of the symptoms is obvious to the doctor from the history, on physical examination, or on “routine” blood tests such as the full blood count, liver and kidney function and on inflammation tests such as ESR and CRP.

3. In other cases, X rays, scans or an ECG are required to achieve a diagnosis.

4. In a relatively few cases the diagnosis emerges only after further invasive tests including biopsies and angiograms.

5. After several further months have passed with no abnormality found to account for the symptoms, the patient is said to have medically-unexplained symptoms.

Step 4 above is bypassed in most patients who are eventually diagnosed as having medically-unexplained symptoms, unless the nature of the symptoms raises concern in the patient or their doctor about specific conditions that require biopsy or angiography for diagnosis.

The exact point at which investigations cease before a patient is diagnosed with medically-unexplained symptoms depends on the concerns of the patient, the nature of their symptoms and their doctor’s judgement (but not necessarily in that order). Many patients are not looking for treatment. They simply want to know that they do not have “something serious”.

Subjective definitions of disease

To the sufferer, “disease” is the sensation of feeling unwell and /or being in pain. This is a subjective definition of disease and does not rely on any tests.

To the doctor and scientist disease is an objective process in which a cause (such as a neoplasm, infection or injury) produces observable organ pathology which is generally accepted as the reason for the sufferer’s symptoms.

The exception is those psychiatric diseases in which a causative biological abnormality is not apparent.

However it is often wrong to conclude that the presence of bodily symptoms without observable organ abnormalities must be due to mental illness. “If the patient’s chest pain is not in the heart then it’s in the mind” is simply wrong. There are conditions other than heart disease that cause chest pain and conditions other than mental illness that cause symptoms without identifiable organ abnormalities.

Disagreement about “no abnormality detected”:

Disagreement can arise between doctors, and between doctors and patients, when attempts are made to attribute psychological causes to medically-unexplained symptoms.

The patient knows that what they are feeling is real and few are happy to be told that their symptoms are “in the mind.”

Some of their doctors may agree with them while others may not. Beliefs on both sides are often strongly-held.

Examples of medically-unexplained symptoms

Most specialities have examples of medically-unexplained symptoms.

Neurologists in particular deal with many patients who have symptoms with few if any associated abnormalities. Tension-type headache, loss of ability to speak, and unexplained limb weakness with no identifiable neurological abnormality are examples. Indeed the University of Edinburgh Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences website states that “Functional disorders are one of the commonest reason for patients to see a neurologist. “

A large number of patients referred for specialist rheumatology opinions, often for musculoskeletal pain, have no relevant abnormalities underlying their symptoms. Examples include nonspecific arthralgia, localised or generalised chronic pain, and fibromyalgia (defined by the 2016 revision of the 2010/11 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria).

Examples of other medically-unexplained conditions include chronic fatigue, unexplained swallowing difficulty and shortage of breath with no abnormalities found on extensive testing.

Irritable bowel syndrome has no causative structural abnormalities in the bowel but may be linked with disordered peristalsis and spasm of colonic smooth muscle.

Pain syndromes:

These are conditions where pain, usually with no identifiable underlying cause, is a major feature.

Sometimes however there is evidence of an underlying cause (such as osteoarthritis or lumbar spondylosis) but the pain and resulting disability appear to be out of proportion to the cause identified.

This is a difficult area for doctors because trying to decide whether or not a patient is feeling pain out of proportion to the cause identified often leads up a blind alley, for reasons that I will explain below.

Is there enough of a causative abnormality to benefit from direct treatment?

For practical purposes, when deciding on treatment of any condition what matters is not whether you think that the patient’s symptoms are proportionate to the amount of abnormality seen but whether there is enough abnormality for the patient to benefit from direct treatment of that abnormality.

This is a very important judgement for any doctor to make. For example a spinal surgeon advising a patient with intense back pain who is clamouring for “an operation to take the pain away” would have to warn the patient that on the basis of their MRI scan showing only minor age-related spondylotic changes and with little likelihood of any other pathology such as lumbar instability, the probability of successful surgery is low.

Patients who have no identifiable pathology underlying their symptoms are far from rare; I recently reviewed my personal rheumatology clinic records of patients whom manage I had seen over a six month period and found that approximately a third of new referrals to my clinics from general practice had symptoms that remained medically- unexplained after all relevant investigations.

What to do when you suspect that a patient might have medically-unexplainable symptoms:

When you have a suspicion early in a consultation that a patient’s symptoms may turn out to be medically-unexplained or functional, you should work to a set of principles in order to avoid misdiagnosis and mistreatment.

At the start of this post I outlined a diagnostic pathway that allows a doctor to progress safely to an eventual diagnosis of medically-unexplained symptoms.

In addition I have found the following approach to be helpful when I suspect that I may be dealing with medically-unexplainable symptoms:

1. I always try to rule out identifiable, particularly directly–treatable causes using the pathway I outlined at the start of this post. I make a diagnosis of medically-unexplained symptoms only after I am satisfied that identifiable, directly-treatable conditions have been actively excluded.

2. In the UK NICE advises at least three months of symptoms in adults with no cause found before diagnosing chronic fatigue syndrome. For painful conditions I prefer longer. I always allow at least six months of symptoms and usually longer without any cause found, before I diagnose the patient’s symptoms as medically-unexplained.

3. Whatever their nature I always investigate recent, consistent symptoms. The more time that passes without any abnormality the less likely the patient is to have a directly–remediable cause for their symptoms. This of course assumes that I have done the right tests! You can reassure patients with medically-unexplained symptoms that with systematic use of modern investigations it is quite rare for a directly-treatable cause of their symptoms to emerge years later.

4. If the patient has a firm belief that their symptoms are due to a specific cause, as long as I think that their belief is reasonable in the circumstances of their case and as long as I am able to investigate it, I will do so.

5. If the relevant investigation is not available to me, or if I think that it is likely that the patient will not accept a negative or indeterminate result I will try to refer the patient to somebody who specialises in the condition for which the patient wants to be tested.

6. If the patient has widespread pain I do at least the following investigations: full blood count, inflammatory markers (ESR and CRP), liver, renal and bone biochemistry, HbA1C, thyroid function tests, ferritin (a measure of iron levels), vitamin B12, folate levels and sometimes vitamin D especially in late winter in the UK. Some of these tests are for conditions that cause fatigue, which often accompanies chronic pain. Probably the commonest cause of mild to moderate long-term ESR and CRP elevation is obesity.

7. As I wrote in my previous post, you should avoid making a diagnosis of SLE without good evidence. When considering SLE I suggest that you base the diagnosis on the 2019 Eular / ACR classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Although these are not strictly diagnostic criteria they provide considerable diagnostic support, with very high degrees of sensitivity and specificity for SLE in different populations.

8. Remember that in the 2019 Criteria a positive ANA is an entry criterion to the diagnosis of SLE. Fewer than 5% of cases of SLE worldwide have a negative ANA. The patient with a negative or weakly positive ANA thus has a very low likelihood of having SLE.

9. Another area of controversy that I have discussed at length in a previous post (“How to Manage Patient Empowerment”) is the interpretation of serological tests indicating the possibility that otherwise-explainable symptoms might be due to chronic Lyme disease.

10. Some pointers to a pain syndrome that I have found helpful:

I always enquire about long-lasting pain brought on by an activity or by focal pressure that in most people does not cause any pain. Such pain is referred to as “allodynic” pain. Long-lasting pain following light pressure over the muscles around the shoulder is an example. Allodynia is common in pain syndromes although not in itself diagnostic of such syndromes.

I ask about a history of irritable bowel syndrome, migraine or (in women) painful periods which can precede more-widespread pain sometimes by decades. If a patient has had all three of these symptoms the chances that they have fibromyalgia increase considerably. Irritable bowel syndrome sometimes develops years before fibromyalgia.

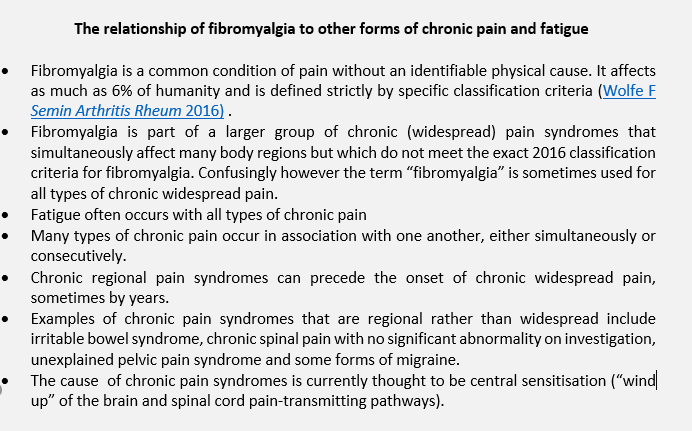

The relationship between fibromyalgia, other chronic pain syndromes and fatigue can be confusing so I have inserted the text box below for clarification:

12. I try not to put any past history of depression on the diagnostic scales when I am considering possible medically – unexplained symptoms. Depression is very common in the population at large and people who have been treated for depression can develop the same diseases as those who have not.

13. At some point one has to ask when to stop searching for directly-identifiable causes for the patient’s symptoms. There may be no clear answer to this question, which is often partly patient-driven. I feel that the search should continue until all reasonable tests have been performed.

14. If I feel that the evidence is strongly in favour of medically–unexplained symptoms I try to be as definite as I can about the diagnosis with the patient and their GP. However if a thorough first round of tests has been normal but I think it possible that an identifiable cause could yet emerge, I will often advise the patient to wait to see if any new symptoms develop, and sometimes to repeat some of the tests a few months later.

15. Some patients are however not willing to wait, so at that point I may refer the patient for a second opinion.

Treatment of medically-unexplained symptoms:

This is a contested topic with many contradictory opinions expressed both by patient groups and clinicians.

For that reason some doctors avoid a diagnosis of medically-unexplained symptoms or pain syndromes. They do not want to become entangled in discussion about whether or not the symptoms are a manifestation of psychiatric illness. This discussion is sometimes precipitated by the patient asking “so do you think that is this all in my mind?”

Other doctors are concerned that they will anger the patient by giving them a diagnosis of what some may regard as “non-disease.” Yet other doctors will be concerned that they have nothing to offer the patient.

My view is that as a starting point every patient deserves to be offered an honest diagnosis and that the doctor can then move on to offer various types of help to the patient. I have found that it can be very reassuring for the patient if I have displayed active involvement in their case by:

· asking what aspect of their symptoms the patient is most concerned about, including the implications of the symptoms for their employment and their future in general, and then focussing on these concerns.

· acknowledging the distress that the symptoms are causing. I try to avoid suggesting that the symptoms are “in the mind” and thus by implication, not real or worthy. Although evidence from neuroscience now suggests that pain syndromes are due to a neurological state called central sensitisation it may be difficult when explaining this to the layman to distinguish this from “it’s in the mind.” To try to overcome this difficulty some practitioners find it helpful to show the patient simple diagrams of ascending and descending pain pathways to explain the concept of central sensitisation.

· offering an explanation about the role of stress if it is clear that stress is exacerbating the intensity of the patient’s symptoms. I have found that it can be helpful to to say something like “we don’t really yet know why this happens, but it sometimes follows, or is made worse by, a time of intense stress”.

· explaining that such symptoms are common and that although cure is unusual, increasing disability is also rare. I always say that the symptoms are likely to wax and wane over the years, with long periods of improvement, but that after presentation there is seldom downhill progression into increasing pain and disablement.

· establishing what the patient wants most, and trying (within ethical and realistic boundaries) to offer it, or helping the patient to achieve what they want.

· suggesting positive self-help measures.

Depending on the symptoms specific treatments may be available; some medications may help with the treatment of chronic pain. Intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy has been suggested as a treatment for functional neurological disorder.

Self-calibrated aerobic exercise and well-administered cognitive therapy may be helpful in the treatment of some cases of chronic widespread pain.

Physical treatments such as stretching exercises using Pilates or yoga, applications of heat, cold, rub-in gels and sometimes TENS to painful areas can improve flare-ups of pain in specific areas.

Medically-unexplained symptoms that have been present for a long time are by definition chronic conditions. As with all chronic diseases the best treatment results are achieved when the patient works actively with a multidisciplinary group of doctors and therapists who focus on the patient’s best interests to mitigate the effects of the condition.

In my next post I plan to discuss defensive medicine and "unnecessary" investigations.